How to make a genius according to László Polgar I

László made 3 geniuses, and it’s not a coincidence.

Ask yourself this: what if there were a formula for genius?

What if it were possible to manufacture a Caesar, a Mozart, or a Picasso in a laboratory? I know there’s been so much debate about this for a long time. However, in my aggressive search for parenting knowledge, I found something that may be worth your time.

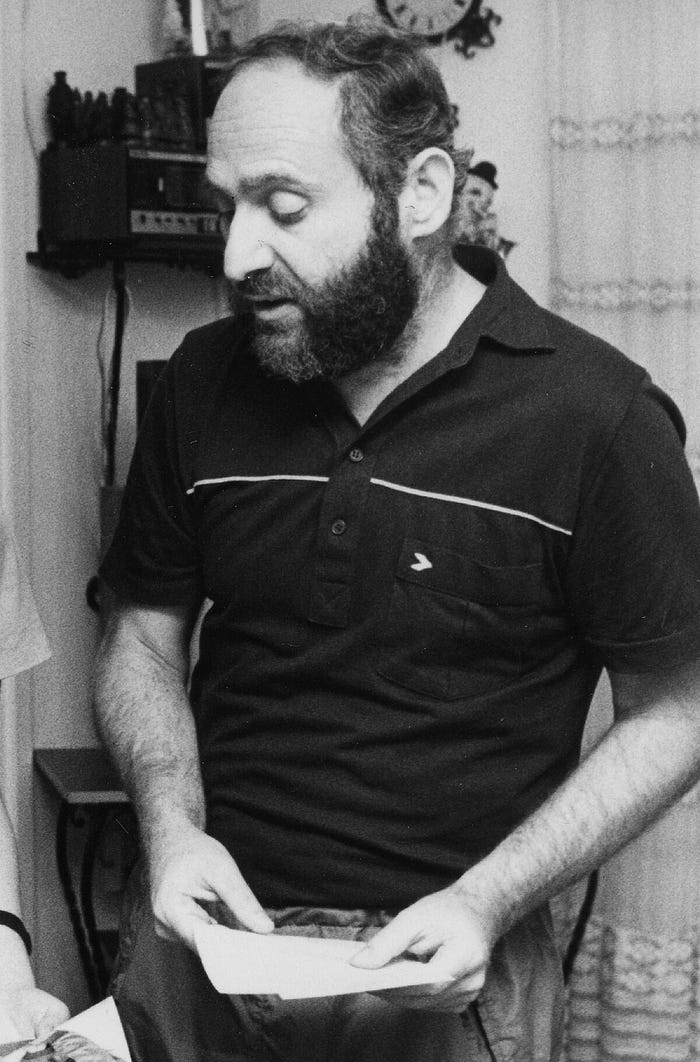

What you will read in subsequent paragraphs is my attempt to condense the genius-raising methods of László Polgar — a man who has found the ingredients to engineer a genius. Although some have questioned his methods, arguing against his proof is difficult. He didn’t just succeed in creating one genius, he made three — which is certainly not a coincidence. So, everyone should at least listen to what he has to say, especially parents.

Before I heard about László, the only Polgar I knew was Judit Polgar, the strongest female chess player. Despite knowing about Judith so early in life, I never devoted time to studying her family until a few years ago. And most recently, I stumbled on a book written by her dad where he laid bare his methodology of raising geniuses.

László Polgár was a Hungarian educational psychologist deeply interested in the idea of genius. He believed that with the right training and education, anyone could become a genius. He asserted that every child born healthy is a potential genius, but whether they achieve this potential depends on circumstances, education, and their efforts. Determined to prove his theory, he made his daughters his test subjects, and they went on to become some of the greatest chess champions of all time.

Naturally, as someone learning to swim in the deep waters of parenthood, this story resonated with me. It not only sheds light on raising geniuses but also offers insights into how anyone can strive for greatness and success in their own lives. Even if you don’t have children, László has some valuable lessons to teach us.

László Polgár was born in 1946 and earned degrees in philosophy and psych-pedagogy — the study of teaching methods. His career as an academic and teacher was successful, culminating in a PhD focused on developing human capabilities, studying genius and how to nurture it. But for László, this was more than just an academic pursuit. After reading over four hundred biographies of renowned thinkers, from Socrates to Einstein, he identified patterns and common traits among them.

Convinced that genius could be cultivated, László decided to put his theory to the ultimate test: raising his children as geniuses. The only challenge he had then was that he didn’t have children yet. He began writing a series of letters to Klara, a Ukrainian foreign language teacher. These letters were not adorned with Shakespearean expressions of eternal love. Instead, they focused on a meticulous and groundbreaking educational experiment that László envisioned for his future children. Fortunately, Klara not only supported his experiment but also shared his vision. They married and committed their lives to raising children in a way that aligned with László’s theories.

The great experiment

László and Klara began their experiment by choosing chess as the field of specialisation for their unborn children. László opted for chess because of its objectivity — winners and losers are clear, unlike disciplines like mathematics or languages, where evaluation can be subjective or influenced by academic politics. With chess, the results would be indisputable.

The Polgárs had three daughters, and László began implementing his method. His goal wasn’t just to see whether genius could be trained but to prove that with the right environment, any child could achieve extraordinary levels of success.

The results were remarkable. The Polgár sisters — Susan, Sofia, and Judit — became chess prodigies. For context, Judit, his last daughter, is often hailed as the greatest female chess player of all time. She received the title of Chess Grandmaster at the age of 15 years and 4 months, at the time the youngest to have done so, breaking the record previously held by former world champion Bobby Fischer.

László’s experiment demonstrated the power of deliberate practice, a structured environment, and a belief in potential over innate talent.

This story has profound implications, not just for parenting but also for how we approach personal development and the cultivation of skills. Whether you’re raising children or striving for greatness yourself, Polgár’s life work offers a compelling argument: genius isn’t born — it’s made.

To buttress the selection of chess as the area of specialisation, chess has rankings which clearly indicate a player’s skill through their win-loss record. Polgár knew that if his method worked, his children would be top-ranked chess players, leaving no room for doubt. Chess leaderboards provide an objective measure — if his daughters appeared there, it would be undeniable proof of their genius.

Hence, Polgár started teaching his daughters chess from a very young age. However, it didn’t go as smoothly as he thought. He faced significant opposition from both political and chess establishments in Hungary, especially because he chose to home-school his daughters.

Why the Polgárs chose home-schooling

As a parent, I have thought deeply about home-schooling and if I had my way, I’d opt for this method. Certainly not because of László — and yes, it won’t be easy. That’s why parenting isn’t for cowards. When asked about his view about homeschooling and why he chose to homeschool his daughters. Here are some of László thoughts about traditional schools below — remember he has a PhD in this subject.

“The way schools work today raises an important question: are they truly helping students achieve their best? When all schools in a country follow the same system, certain issues become clear. In a typical traditional school, there are always a few exceptional students, many average students, and some who are below the average level. Most of the average students are closer in ability to the below-average ones than to the top performers.”

This scenario László describes ultimately leaves most teachers with no choice but to focus their lessons on the average students. A teacher cannot create lessons that cater to the few outstanding ones, even if they want to. Neither can they design lessons for the students at the bottom of the class. For the top-performing students, this lack of lessons that fit their intellect can make class boring because the material doesn’t challenge them or spark their interest.

László further buttresses this in his book, “Even with the best intentions, teachers face limits. They cannot adapt their lessons to fit every student’s needs, especially in a large class with varying abilities. As a result, they focus on managing the group as a whole, which often means the potential of individual students is not fully developed.”

László’s dislike for traditional school didn't end there. He also argued that traditional schools are often disconnected from real life. They function like closed-off spaces, far removed from everyday concerns such as family, local community issues, or larger societal problems. This gap makes it harder for students to see how their learning applies to the real world.

According to him, his three daughters who never attended traditional schools, grew up in an environment closely connected to daily life. Their learning came naturally through experiences that were relevant to the world around them.

Another problem with traditional schools that László mentioned is that they struggle to inspire students to love learning or aim for great accomplishments. Many schools do not encourage creativity or curiosity and fail to nurture students as independent thinkers or active members of their communities. They miss the opportunity to fully unlock the potential in each child.

László’s assertions lead us to an important question: are schools, as they are now, truly preparing students for life? If not, how can we improve them so that all children have the chance to succeed, grow, and contribute to the world in meaningful ways? It’s a challenge worth addressing for the sake of every child’s future.

László again

Worth mentioning is that when László was home-schooling his daughters, Hungary was a communist country where private education was frowned upon as elitist and contrary to the principle of equality. If regular private education was viewed as problematic, you can imagine what László’s idea of creating geniuses would be then. It was viewed as elitist and anti-communist.

Polgár had to fight persistently for the right to educate his daughters, tirelessly petitioning and arguing that his methods would ultimately benefit Hungary and communism. Despite the challenges, he was determined and often operated in legally ambiguous areas to continue his work.

The Hungarian chess establishment also opposed him, partly because he had no sons, as chess was viewed as a male-dominated activity. Women, particularly young girls, were discouraged from seriously pursuing the game. Despite this, Polgár committed himself entirely to tutoring his daughters, sacrificing financial security in the process. The family lived modestly in a small apartment in Budapest, with Polgár dedicating what little resources he had to purchasing chess books and creating an extensive card filing system to catalogue various chess positions.

His youngest daughter, Judit, later described their household as being entirely centred around chess. The results of Polgár’s dedication were remarkable. All three daughters became highly successful chess players. The eldest, Susan, born in 1969, began her career early, winning the Budapest under-11 girls’ championship at age four. She defeated her father at chess by age five and started beating accomplished players at the local chess club shortly after. By 15, she was the top-rated female chess player globally and later became the third woman ever to earn the Grandmaster title.

Susan mainly competed in men’s tournaments, as Polgár encouraged this approach to ensure she faced tougher competition. Eventually, she entered the women’s tournaments and won the Women’s World Championship in 1996. She also won the U.S. Open Blitz Championship twice, in 2002 and 2005, competing against a field of top-ranked players, including Grandmasters.

The second daughter, Sofia, born in 1974, also achieved impressive milestones. In 1986, she was crowned the World Junior Under-20 Rapid Champion and nearly won the boys’ under-14 championship, making her the de facto girls’ champion. At just 14 years old, she triumphed in an elite chess tournament in Rome, defeating many seasoned Grandmasters.

This event became known as the Sack of Rome. One of the Polgár sisters ranked among the top female chess players globally and, in 1994, finished second in the World Junior Chess Championship — not in the girls’ category, but in the overall championship. However, her career was considered the least successful of the three sisters.

In 1996, she won the gold medal at the Women’s Chess Olympiad — the only gold medal of her career. This was largely because her more successful sisters were not competing in that event. Talk about Ronaldo and Messi playing in the same generation. While Sofia Polgar might be regarded as less accomplished compared to her siblings, she is undoubtedly one of the top 10 or 20 greatest female chess players in history. Just imagine! Nevertheless, being the third-best player in her family diminishes the perceived brilliance of her achievements.

In her early teens, she developed a passion for art and later shifted her focus away from chess to pursuits like painting, interior design, and full-time motherhood, raising her two children.

The youngest of the sisters, Judit, born in 1976, is widely regarded as the greatest female chess player of all time. Her dominance in the field is unparalleled. She won her first international chess tournament at age nine and defeated a Grandmaster by 11. By 14, she was the youth champion of the world, triumphing in both the boys’ and girls’ categories. At 15, she achieved the prestigious Grandmaster title. In 2005, at 29, she peaked at world rank number eight, becoming the first and only woman to qualify for the men’s World Title Championship. Judit held the top ranking in women’s chess for over 20 years, only relinquishing it upon her retirement. Talk about Serena Williams in tennis.

Their father, László Polgár, is often credited for the sisters’ remarkable achievements. Many speculated that his methods might have been harsh or unethical, perhaps pushing his daughters to the brink. However, the sisters unanimously recall a happy and balanced childhood. Even Sofia, who shifted her focus to art and motherhood, reflects fondly on her chess career and has no regrets about her father’s approach.

So, what is László’s genius raising method and how can anyone replicate it if they want to? That’s what the second and concluding part of this writing will be about next week.

I will also share a link to get a free copy of László’s book for your reading pleasure. Don’t worry, it’s not illegal. It’s straight from the blogger than financed it’s translation to English.